This is a replica of the Workout Barbie from Toy Story 3.

It appears that most decades have been marked by some sort of moral panic outbreak. Most of the time, the hysteria stems from adults fearing that some object of pop culture is harmful in one way or another to the younger generation. A February 6, 2012 article found on Reuters.com, “Aww, man! Bart Simpson joins Barbie in Iran ban”, addresses the recent move by Iran to ban the selling of “The Simpsons” dolls, as well as Iran’s last month decision to crack down on Barbies. The article states that: “The Simpsons are corroding the morals of Iranian youth” (“Aww, man! Bart Simpson joins Barbie in Iran ban”). In the article, Mohammad Hossein Farjoo, Secretary for Policy-making at the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, expresses his dissatisfaction with the longest-running American sitcom, “The Simpsons”. Farjoo is unwilling to promote this animated sitcom, and in turn has put a ban on the importation goods associated with it. The article mentions Farajoo’s disapproval of the values held by the Simpson family, which are “self-centered and irreligious” (“Aww, man! Bart Simpson joins Barbie in Iran ban”). The selfish and inappropriate conduct of one of America’s most well-known families, the Simpsons, is contrary to Iranian standards; therefore, Iranian officials deem it necessary to take all precautions in order to avoid losing their youth to “Western intoxication” (“Aww, man! Bart Simpson joins Barbie in Iran ban”).

All 5 members of the Simpson family from the animated sitcom, "The Simpsons".

This fear of an animated television show corrupting the Iranian youth parallels a great deal with the comic book scare of the 1950s in America. In the 1950s, many adults feared that comic books were negatively influencing the younger generation, as was mentioned in David Hajdu’s The Ten-Cent Plague. Hajdu quotes a statement made by Chief Chris K. Keisling: “They [mothers] are helpless to protect their children from the lurid booklets through [which] cavort half-nude women…[and which]…belittle law enforcement and glorify crime” (Hajdu 89). American adults feared that adolescents were easily influenced, and thus believed that the content and values found in comic books resulted in misbehavior and juvenile delinquency. As a result, attempts were made to ban certain comics books and write up legislation that controlled the content written in them. This is quite similar to the current events taking place in Iran, which are driven by Farjoo and others who share his concern with “The Simpsons”, and their potential to corrupt the Iranian youth by instilling values that are disagreeable with those of the Iranian culture.

Iran has taken further action to protect their traditional values, such as their previously established ban on the importation of Barbies. The apparel, or rather lack of apparel, worn by Barbies differs a great deal from the traditional dress code of an Iranian woman; the article states: “The American doll’s full figure and revealing wardrobe particularly offend Iran’s leaders, who decree that women must be fully swathed in loose-fitting clothes in public” (“Aww, man! Bart Simpson joins Barbie in Iran ban”). The Barbie doll is offensive to Iranian officials who do not want to risk young girls being influenced by their half-dressed Barbie doll, for fear that such a toy might prompt girls to question or even rebel against the conservative dress code that their culture expects of them. Sharing the same concern, the Hajdu passage mentioned above addresses the American adult concern with the images of scandalously dressed women that adolescents were exposed to in comic books.

Both the Iranian adults of today and the Americans of sixty plus years ago share the belief that some object of pop culture, whether it be television shows, dolls, or comic books, are having negative impacts on the younger generation. Neither culture, American or Iranian, would or will stand by and allow these pop culture sensations to “brainwash” their youths into acting in ways adults perceive(d) to be shameful without putting up some sort of fight to try and stop it.

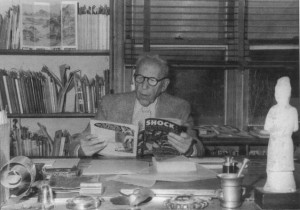

Here’s a link to the website I showed you in class today, all about Seduction of the Innocent, Frederic Wertham, and the comics panic.

Here’s a link to the website I showed you in class today, all about Seduction of the Innocent, Frederic Wertham, and the comics panic.